Chapter 9 - Part 2

Los Alamos- 1980-1983

Family

(Both) We heard about a circus and performing arts summer camp that seemed perfect for Cassidy, who was already fascinated by physical theatrics and clowning. It was called Camp Winnarainbow, held at the Lama Foundation, a spiritual retreat center north of Taos, NM, directed by Wavy Gravy and Surya Singer. With some financial help from Molly’s parents, Cassidy attended a one week session in 1980 or 81, and then in subsequent summers, after the camp moved to Sunrise Springs near Santa Fe, he attended some two-week sessions. This was formative in Cassidy’s life, teaching him juggling and clowning arts and initially connecting him with Wavy Gravy. Years later, when Cassidy was at Sonoma State University, he ran into Surya Singer (now Ron Singer) who reconnected him with Camp Winnarainbow in California, where he began working as a camp counselor and teacher during the summers, with reverberations throughout the rest of Cassidy’s life. (More on this in later chapters.)

We had some great family trips during these years, including a trip to Grand Canyon, several camping trips in New Mexico, and two trips to Cave Creek in the Chiricahua mountains in southeastern Arizona–one in 1980 when Ish came with us, and another in 1982 with Tim and Zana Burns and their 18 month old daughter Ashley. Cave Creek holds a special place in Molly’s family history, because her mother, Emma Lou, camped there every summer in her childhood with her mother and two sisters, during the time they lived in nearby Douglas, Arizona.

We thoroughly enjoyed our times there, hiking, cliff climbing, playing in the river. We weren’t prepared, however, for javelinas coming to our campsite on one occasion, prompting Chica to go barking after them before we managed to call her off. Javelinas are very fierce and aggressive animals who could make quick work of our little dog. On another occasion, we enjoyed even less trying to clean up poor Chica after she was sprayed by a skunk.

Molly’s older niece Jenene graduated from high school and joined the Navy in 1981. Molly’s sister Judy, brother-in-law Smitty, and their younger daughter Lisa, age 15, then moved to Manhattan Beach, California, after many years in Los Alamos. We were able to visit them a few times, often in conjunction with a conference in the vicinity. The Smiths’ marriage had been on the rocks for some time. Judy found an excellent therapist with whom she worked for several years, healing some profound wounds from her childhood and preparing herself to leave Smitty, which she finally did in 1984.

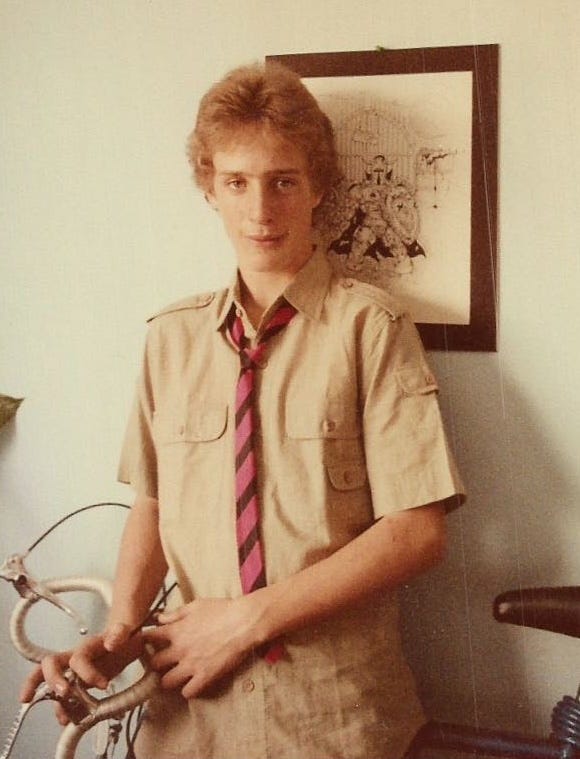

(Both) Cass is in eighth grade at Cumbres Junior High School in Los Alamos, still wearing jeans and tee shirts, and with fairly rumpled hair. He is not a happy camper, being teased at school and feeling down on himself. He is in a particularly bad place one weekend day as we two are headed to Santa Fe for some errands, including a haircut for Jim. We offer to take him with us, but he refuses. Something prompts us to pull rank and order him into the car against his protests. Jim’s hair cutter has time to give Cass a classy haircut–probably the first professional haircut he’s had. Afterwards, we take him shopping for new duds: nice slacks, shirts, and even a tie. He is transformed, not only in appearance but apparently also in spirit! Years later, he would tell people that although both his parents were therapists, when he was depressed our intervention was to take him shopping!

(Molly) When Ish and Greg are in high school, I hear a story from Greg that sends me to the vice principal’s office in Ish’s defense. Apparently Ish had kissed his girlfriend goodbye in the school parking lot, violating a rule against “public displays of affection,” and when the parking lot monitor admonished him, Ish walked away in disgust. The monitor notified the vice-principal who confronted Ish in the school lobby, whereupon Ish once again walked away. He ended up in the vice-principal’s office, to which his mother had also been summoned, and was suspended for a day. During this meeting, Ish translated for his mother, who spoke very little English, and the v-p reportedly objected, saying, “Speak English.”

I am disturbed by this story of what seems to be an overly punitive response to a very minor infraction and decide to intervene, because I believe that Ish’s mother–having fled with her family from a violently oppressive regime in Chile–might be afraid to protest. I know the vice-principal from the UU Church and assume we have similar values. We have a good talk, during which I object not only to the culturally offensive response to Ish’s translating for his mother, but to the rule about “public displays of affection” itself. I ask Skip if he ever kisses his wife goodbye in a public place; why shouldn’t students have the same right? Of course making out on the front lawn of the high school is inappropriate, but it seems overkill to have a rule outlawing any kind of affection.

I am not able to rescind Ish’s suspension, but hope I have at least challenged the school administration’s rule, punitive reactions, and cultural biases, while letting Ish know I care enough to stick up for him.

Molly and psychosynthesis

(Molly) In addition to my on-going and very fulfilling work with Intermountain Associates for Psychosynthesis (described in Chapter 9 Part 1), I presented the basics of psychosynthesis to social and professional organizations, as well as teaming up with other mental health professionals to offer a variety of workshops and support groups–and here neither my memory and nor my journals provide specifics, only vague hints.

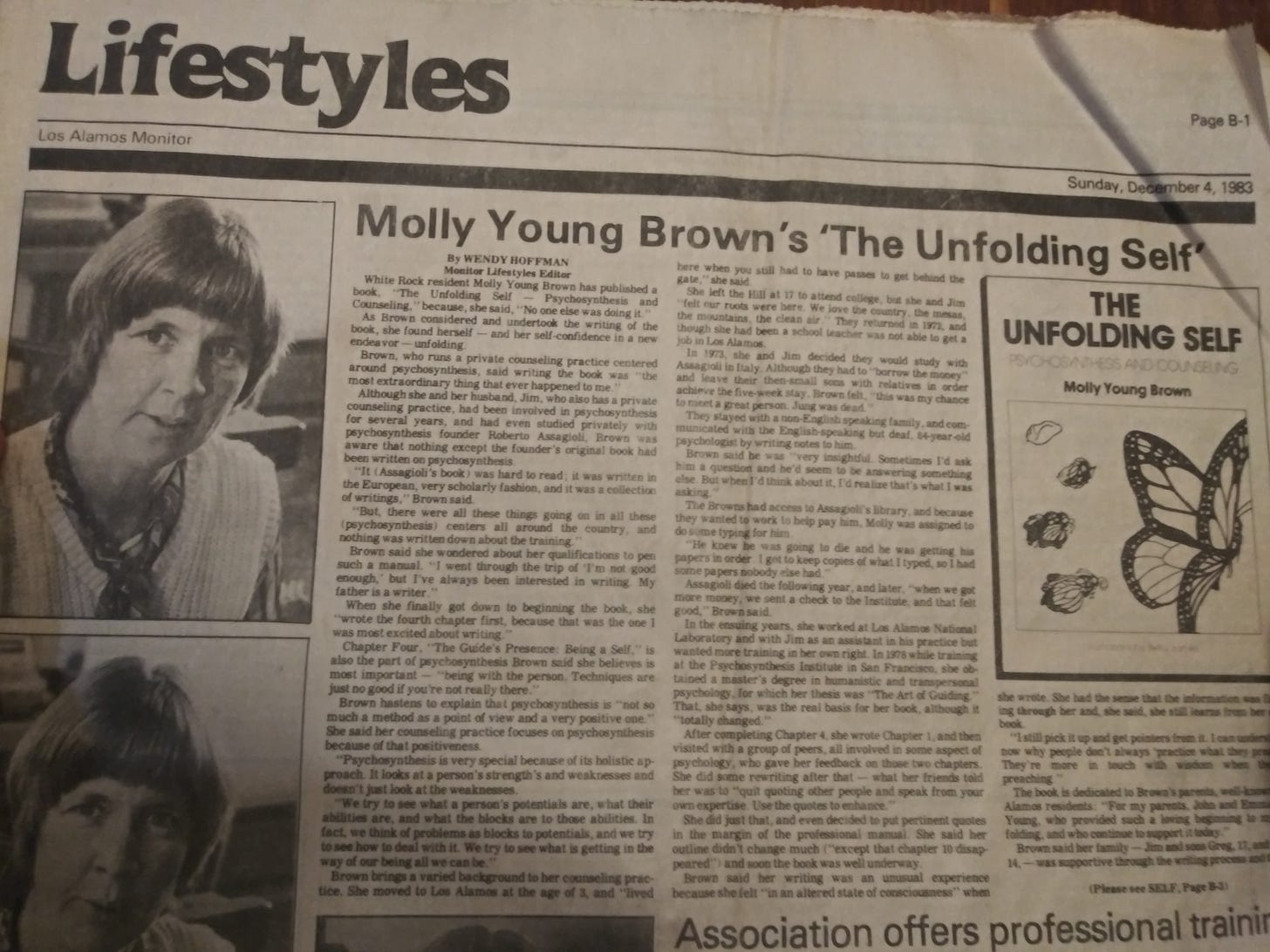

The Unfolding Self

(Molly) It took me three years to write The Unfolding Self, which I finally self-published in 1983. Later I found out that Piero Ferrucci, one of Assagioli’s closest colleagues, was also inspired around the same time to write a book. Fortunately, our books turned out very different. Ferrucci’s What We May Be (published in 1982) is addressed to anyone interested in personal and spiritual growth, while my book was intended primarily as a guide for counselors and therapists who want to bring psychosynthesis into their professional practice.

I tried without success to find a publisher for the book (a pattern that has been repeated several times in my writing life). Eventually, I decided to self-publish, which was a major undertaking in the days before desktop publishing. Doug Russell agreed to let me publish the book under the name of his Psychosynthesis Press. I hired someone to enter the manuscript into a word processor because only a few professionals owned one in those days. Then I hired Marilyn Gong in Santa Fe to design and layout the book, a painstaking task that we worked on together–it was actually quite satisfying, even fun. We used the print-out of text (already including headings and the wide margins I wanted) but had to physically cut the printout when we wanted to start a new page or fit in an illustration, sometimes having to move just one or two words to below an illustration or onto the next page. My friend Betsy James created beautiful full page drawings to head up each chapter. We really created a beautiful book!

Over time, The Unfolding Self found its way into the world, in spite of very limited marketing. Many of the training centers then blossoming in North America and Europe used it as a major text; it was eventually translated into French, Swedish, and Japanese. I was so gratified to know the book made a significant contribution to the field. In 2004, a revised edition, now titled Unfolding Self: The Practice of Psychosynthesis, was published through Helios Press (an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing) and remains in print to this day, still used in several psychosynthesis training programs.

Since 1983, dozens of books on psychosynthesis have been published, including at least six by Piero Ferrucci, and my book Growing Whole–more on that later.

Molly’s Private practice

(Molly) I gradually developed an individual psychosynthesis counseling practice, mostly working in the Room. There was no licensing for mental health counselors in New Mexico at that time, only for clinical psychologists with PhDs. To keep out of trouble, I was careful not to call myself a therapist or even a counselor (“life coach” wasn’t an option yet). I presented my work as “psychosynthesis guiding, an educational process that people can apply to their lives as they choose.”

However my counseling practice also had some major challenges. In 1983, a man whom I had been counseling for a few months shot his wife, her friend, and then himself. The friend and my client died, and the wife nearly died but managed to pull through. A colleague in Los Alamos phoned me with the news as I was finishing up a workshop with Walter in Albuquerque. I was devastated, wondering how I could have missed the cues of what my client was planning. And he had planned it, buying a gun in Santa Fe a week or so before. The only comfort I found was in talking with the Unitarian minister who lived next door to my client. He had engaged in a long conversation with my client the night before the murder/suicide, and had no hint of what was about to take place.

Looking back now, it’s hard to remember how this changed my work, but I know it did. For one thing, from then on I insisted that clients in any kind of serious distress make a no-suicide pact with me; if they refused, I referred them to another professional. I also insisted that no guns be kept in the home of anyone I was working with. Of course I couldn’t check up or enforce this, but it did establish a boundary for my work with people, and let them know how seriously I took any hint of potential violence.

In one situation that I look back on with some satisfaction, a client reported that her boyfriend (with whom she and her small children lived) was “disciplining” her children, one only 18 months old, the other about three. When I told her that I was bound by law to report possible child abuse to Child Protective Services, she immediately moved out. I believe she needed only an authoritative nudge to overcome his intimidation and take action.

Conferences and psycho-spiritual pursuits

(Molly) Because I was working a flexible schedule, I was able to take time off to attend several conferences in the early and mid-1980s, sponsored mostly by the Association for Humanistic Psychology (AHP) and the Association for Transpersonal Psychology (ATP). These conferences fed my passion for more encompassing and positive world views than those I found at the Lab and in most of the Los Alamos community. I also attended a conference sponsored by the Institute for the Study of Conscious Evolution, where I heard Barbara Marx Hubbard speak about her amazing vision of human potential.

I had learned that the School for Esoteric Studies in New York City was connected to Assagioli’s esoteric spiritual interests and decided to take their correspondence course to continue my study related to psychosynthesis. It was a demanding undertaking: I was supposed to study and meditate at the same time every morning, and at regular intervals, send in my responses to questions related to what I read. I can’t remember how often, now, but recall it’s being quite demanding on my time and attention. I kept at it for 7 months before I ran aground. One of the readings referred to “the inferior races” and when I objected to this, I received what I considered to be a patronizing rationalization that did not acknowledge the underlying racism. It was something to this effect: “Oh, this refers to the ‘lemurians.’ Don’t worry about it.” This was the last straw, after having struggled all along with the arcane language and worldview. I discontinued the course immediately.

In 1983, our friend Tom Yeomans, along with John and Anne Weiser, organized the first International Psychosynthesis Conference in Toronto. Of course I attended this historic and inspiring event. I recall hearing Peter Russell speak about “the global brain” (the title of his book published the same year)--and how his vision expanded mine. I remember Mark Horowitz having us all breathe together and contemplate how all living beings breathe together–a powerful experience of interconnectedness.

Following that conference, I visited Tom and Anne Yeomans in Concord, Massachusetts and Elena Maulsby in New Hampshire. That was my first visit to New England and I was enchanted! It was also a very healing solitary vacation for me, still recovering from my client’s murder/suicide a year before.

That October, I participated in a “Long Dance” under the leadership of Elizabeth Cogburn. She had obtained the use of the large reconstructed underground kiva at Aztec Ruins National Monument in Aztec New Mexico, quite near to Flora Vista where Donna and Tex lived with Chris (three years older than Greg) and Rusty (Greg’s age). Jim, Greg, and Cass stayed there while I took part in the preparations and the ceremonial dance from dusk to dawn.

In the kiva, the two dozen or so people formed two big circles around a huge mother drum, drummed by several people seated around it. One circle moved clockwise with steady, even steps; the other moved counterclockwise. We could join either circle for slow steady movements, and from time to time move into the center of the circle for improvisational dancing. There was an adobe bench running all around the walls to which we could retire when we needed rest–still trying to stay awake, however! I remember the thrill of seeing the early light of dawn, feeling both tired and exhilarated by the experience of dancing–and praying–all night.

Friendships

(Molly) My friendship with Susan (now Morgan) Farley continued to deepen. Susan channeled a being called “Gabriel” with whom I often consulted. After a while, I decided to try channeling myself, which led to my doing what I called “guide writing” over the next couple of years. So much wisdom and guidance poured through this way, into the journals I still have. This became a period of tremendous growth and insight that I realize has shaped me profoundly to this day.

Joseph Rael - Beautiful Painted Arrow

(Jim) An emerging aspect of my project with the Indian Health Service that turned out to be super-fulfilling was traveling to distant parts of the service area to confer with staff of outlying clinics about the program. I offered group presentations on the fundamental principles of stress, its role in illness, and the use of biofeedback and related techniques for remediating its adverse effects. This aspect was augmented when Joseph Rael was hired to maintain a program for preventing and treating alcoholism and other addictions in the indigenous population served by the Santa Fe Service Unit. He had moved into the office adjacent to mine. (Synchronistically, that very position and office had been occupied by my friend and colleague Charles King, who had taken over the program coordinator position in Los Alamos that I had left a couple of years before to begin my doctoral studies in the Bay Area. We were privileged to be co-workers again until he left to take a higher-paying position with a New Mexico state program.)

Joseph, whose ancestry included both Pueblo (Picuris in his case) and Southern Ute natives, had interests very similar to mine, and we became friends as well as colleagues. I accompanied him to Picuris Pueblo on a couple of occasions as he laid the foundation for creating a holistic health center there incorporating both indigenous and progressive health practices. Such a center would not only have provided valuable services–such as biofeedback training– to the people of Picuris, but would also have widened the scope of my study. Unfortunately, funding for that center remained elusive, and it did not get off the ground.

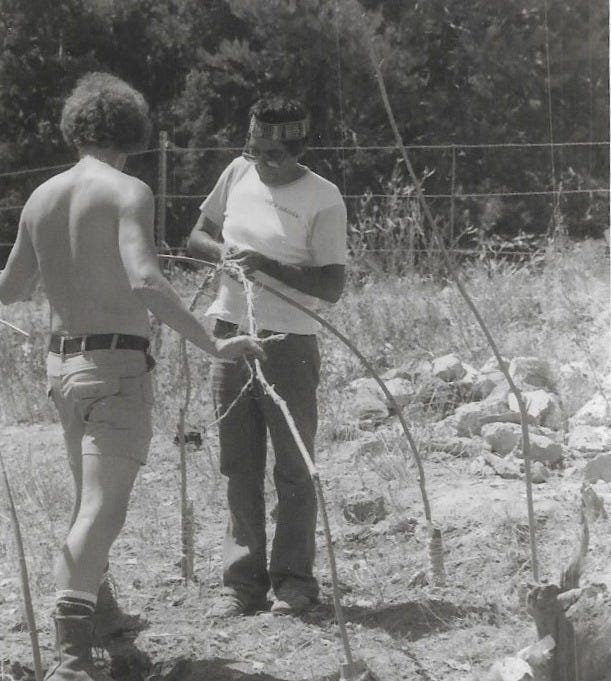

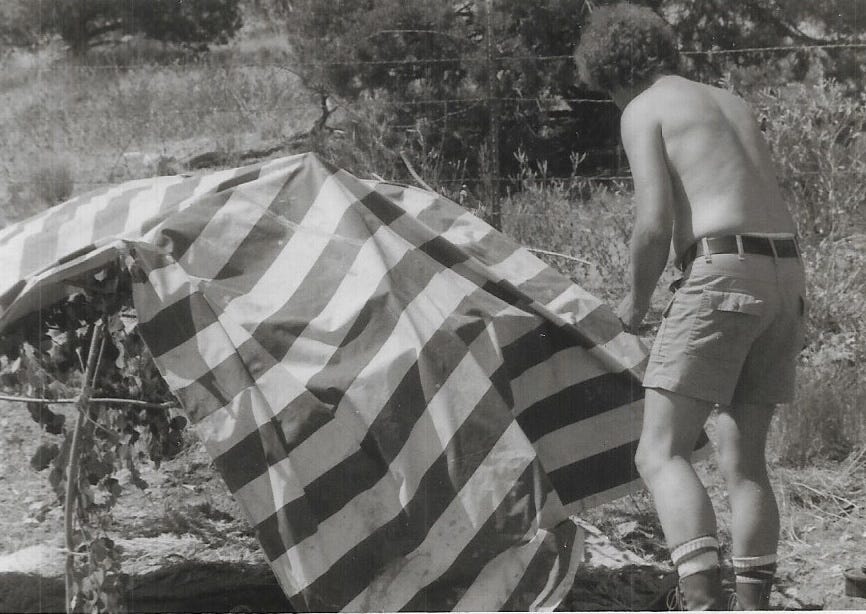

On his own time, Joseph was very active in furthering the use of sweat lodge ceremonies as both a spiritual and health-enhancing practice. He invited me to participate in some of these ceremonies, and I did so gratefully on several occasions. He even offered to help us build a sweat lodge behind our house in White Rock, a gift we enthusiastically accepted. Following his instructions, I gathered green willow branches of a specified length and thickness from wetlands adjoining the Rio Grande several miles from our White Rock home. His instructions included following the shamanic traditions of his people, such as expressing gratitude to the willows and tying a small packet of tobacco to each tree from which branches were taken, in exchange for its contribution to the coming ceremonies. A work party was organized one weekend to construct the dome-shaped lodge. Then Joseph led the ceremony to initiate that lodge one splendid summer evening. We invited several close friends to participate in the ceremony, which was followed by a pot-luck supper.

It was a unique and fulfilling experience for all of us. And for Molly and me, it marked the first stage in a long series of such experiences with Joseph Rael (aka Beautiful Painted Arrow).

Besides accompanying Joseph to Picuris Pueblo, I also traveled to his original home, the Southern Ute reservation in the southwestern corner of Colorado, to confer with indigenous health professionals there and conduct workshops in holistic health principles and self-mastery techniques. I did the same on the Jicarilla Apache reservation and–more often (because it was a much shorter drive from Santa Fe)--at San Juan Pueblo.

Two other important friendships

(Jim) I have so much appreciation and gratitude for my association with Joseph Rael (which continues even now at our advanced ages) . Without doubt the most lasting and gratifying outcome of that association began one day as I walked down the short hallway toward my office, which was adjacent to Joseph’s office. His door happened to be open and I noticed as I walked past that he was talking with a visitor. I glanced in, expecting to see another co-worker, and saw instead an unfamiliar woman’s face, a face so attractive that I had a strong impulse to stop and gawk. I managed to be cool enough not to do that, but slowed down a bit approaching my own office door to get a better look–which confirmed my instantaneous impression that Joseph was indeed conversing with a lovely woman.

I soon found out that her name was Susan Scott, that she was a social worker and writer, and that Joseph had arranged to have her write a grant proposal for him. Over time, after he introduced us, I filled her in on the Self-Mastery Program, showed her the biofeedback facility and demonstrated that aspect of data collection. So a friendship began forming that has continued to deepen over the decades since.

About midway through my tenure with that program another very attractive woman appeared who had been drawn to my work there in a most unusual way. Claudia Hallowell, who had been consulting with the Santa Fe Police Department and Fire Department on issues pertaining to stress management, phoned me at my office to inquire about the work I was involved in. I invited her to meet me there, and over a period of time I walked her through various aspects of the program, as I had done with Susan. As we became better acquainted, Claudia shared the circumstances leading up to her contacting me.

She said that she had long experienced an unusual degree of intuitive perception, which included input from paranormal sources. A conviction had recently emerged in her that she needed to find a way to study her brain waves, which led to her searching for a resource to accomplish that. She had been unable to locate such a resource. One day, as she was meditating, she envisioned a telephone number and experienced a strong feeling that she was to call that number. When she followed that prompting it turned out to be the number for the Santa Fe Indian Hospital, and she inquired about brainwave measurement there. She was given the number for my office, phoned me, and that was the portal to a friendship between us that continues to the present.

We had quickly discovered common ground in our experience and fascination with extraordinary states of consciousness. After completing the research I was doing for the Indian Health Service I resumed working on my doctorate at the Humanistic Psychology Institute. I was then at the stage of designing and conducting research for my dissertation–the final phase of that process. It turned out to be a study of brainwave patterns involved in various non-ordinary states of consciousness. I recruited several people experienced in either “channeling” or meditation to be subjects in the study and–here’s the kicker–Claudia was one of those subjects.

So it took a few years to germinate, but Claudia’s psychic vision of a phone number one fateful day in Santa Fe led at last to having her brain waves studied! And, stemming from that fruition, our association continues even now in an intensive, ongoing dialogue centered on her paranormal revelations and our joint fascination with understanding and advancing human consciousness .

Thus two robust friendships emerged directly from that fortuitous IHS employment–personal and collegial relationships that have lasted and grown right up to the present. Both friendships focus on shared life-work issues, but the issues addressed in each of them have unique features. Susan and I, for instance, both have advanced professional credentials in the field of applied psychology, while also being dedicated to creative writing (especially poetry). Claudia and I, on the other hand, focus our explorations on deeply esoteric levels of being and understanding, the nature of the cosmos, and our developing trajectories toward unfoldment as enlightened beings.

Alongside these distinctions between overall focus in each relationship, I also notice some remarkable similarities of dedicated interest. Two stand out particularly: 1) understanding and experiencing qualities of soul, and 2) exploring and marveling over the phenomenon of synchronicity. After all, synchronicity permeates the circumstances that gave rise to both enduring friendships.

It almost seems too obvious to mention, but for the sake of completeness I must acknowledge that both these friendships exist in a powerful field of affection, of life-affirming love.

Frances Robertson

(Both) Frances, who had worked with Jim as a consultant at the Los Alamos Council on Alcoholism in the 1970’s, remained a good friend and wise Elder for us both. More than once, she invited the two of us down for dinner in her charming adobe home near Nambe. Molly would seek her out for counsel in times of confusion and anguish, even after Frances (a lifelong smoker) became ill with throat cancer. Molly would sit at the foot of her bed and pour out her heart. Sometimes we would stop by Frances’ home on our way back from Santa Fe or Taos to see how she was doing and find out if there was anything we could do for her.

As the cancer progressed and it became clear she would not survive, her sister Natalie, a nurse, came to care for her. So it was that on our return one day from Santa Fe, we dropped by to check her condition and discovered that Frances was near death. She hadn’t been able to eat or drink for several days and was in a terminal coma.

Our kids were with Molly’s parents, so we were able to stay, along with Janis Siemon (who drove down from Los Alamos when we phoned her), Frances’ landlady (a good friend and fellow AA member), and Natalie. Molly found and lit candles, placing them all around the room, while Janis put on Frances’ favorite music, Pachelbel’s “Canon.” We took turns sitting at her bedside, holding her hand and singing or speaking our love to her. Late that evening, when she took and released her last breath, we all heard it and spontaneously let out a collective cheer at her release. Her presence filled the room and we felt blessed by her love.

During her illness, Frances had been visited several times by her friend Ram Dass, who had assured her: “Death is safe.” That day and evening we learned deeply the truth of his benediction.